Sep 27, 2012 | Abuses of Power, Activism

Smartphones can be a cop’s best friend. They are packed with private information like emails, text messages, photos, and calling history. Unsurprisingly, law enforcement agencies now routinely seize and search phones. This occurs at traffic stops, during raids of a target’s home or office, and during interrogations and stops at the U.S. border. These searches are frequently conducted without any court order.

Smartphones can be a cop’s best friend. They are packed with private information like emails, text messages, photos, and calling history. Unsurprisingly, law enforcement agencies now routinely seize and search phones. This occurs at traffic stops, during raids of a target’s home or office, and during interrogations and stops at the U.S. border. These searches are frequently conducted without any court order.

Several courts around the country have blessed such searches, and so as a practical matter, if the police seize your phone, there isn’t much you can do after the fact to keep your data out of their hands.

However, just because the courts have permitted law enforcement agencies to search seized smartphones, doesn’t mean that you—the person whose data is sitting on that device—have any obligation to make it easy for them.

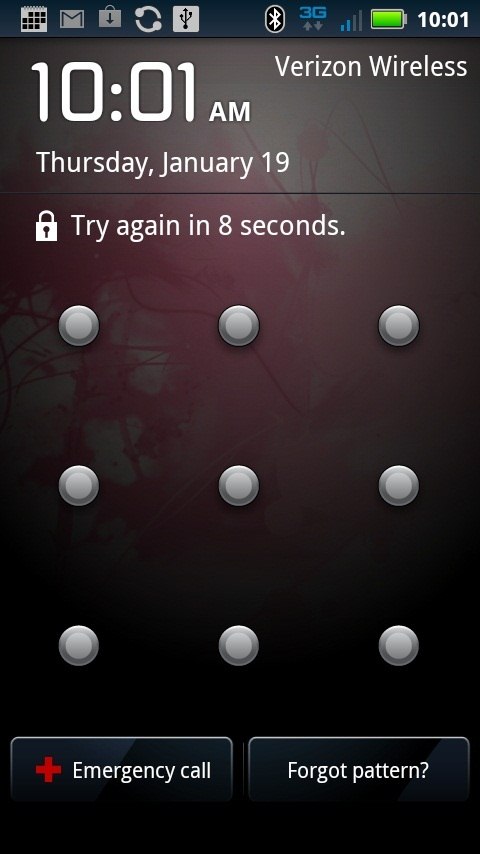

Screen unlock patterns are not your friend

The Android mobile operating system includes the capability to lock the screen of the device when it isn’t being used. Android supports three unlock authentication methods: a visual pattern, a numeric PIN, and an alphanumeric password.

The pattern-based screen unlock is probably good enough to keep a sibling or inquisitive spouse out of your phone (providing they haven’t seen you enter the pattern, and there isn’t a smudge trail from a previous unlock that has been left behind). However, the pattern-based unlock method is by no means sufficient to stop law enforcement agencies.

After five incorrect attempts to enter the screen unlock pattern, Android will reveal a “forgot pattern?” button, which provides the user with an alternate way method of gaining access: By entering the Google account email address and password that is already associated with the device (for email and the App Market, for example). After the user has incorrectly attempted to unlock the screen unlock pattern 20 times, the device will lock itself until the user enters a correct username/password.

What this means is that if provided a valid username/password pair by Google, law enforcement agencies can gain access to an Android device that is protected with a screen unlock pattern. As I understand it, this assistance takes the form of two password changes: one to a new password that Google shares with law enforcement, followed by another that Google does not share with the police. This second password change takes place sometime after law enforcement agents have bypassed the screen unlock, which prevents the government from having ongoing access to new email messages and other Google account-protected content that would otherwise automatically sync to the device.

What this means is that if provided a valid username/password pair by Google, law enforcement agencies can gain access to an Android device that is protected with a screen unlock pattern. As I understand it, this assistance takes the form of two password changes: one to a new password that Google shares with law enforcement, followed by another that Google does not share with the police. This second password change takes place sometime after law enforcement agents have bypassed the screen unlock, which prevents the government from having ongoing access to new email messages and other Google account-protected content that would otherwise automatically sync to the device.

Anticipatory warrants

As The Wall Street Journal recently reported, Google was served with a search warrant earlier this year compelling the company to assist agents from the FBI in unlocking an Android phone seized from a pimp. According to the Journal, Google refused to comply with the warrant. The Journal did not reveal why Google refused, merely that the warrant had been filed with the court with a handwritten note by a FBI agent stating, “no property was obtained as Google Legal refused to provide the requested information.”

It is my understanding, based on discussions with individuals who are familiar with Google’s law enforcement procedures, that the company will provide assistance to law enforcement agencies seeking to bypass screen unlock patterns, provided that the cops get the right kind of court order. The company insists on an anticipatory warrant, which the Supreme Court has defined as “a warrant based upon an affidavit showing probable cause that at some future time, but not presently, certain evidence of crime will be located at a specific place.”

Although a regular search warrant might be sufficient to authorize the police to search a laptop or other computer, the always-connected nature of smartphones means that they will continue to receive new email messages and other communications after they have been seized and searched by the police. It is my understanding that Google insists on an anticipatory warrant in order to cover emails or other communications that might sync during the period between when the phone is unlocked by the police and the completion of the imaging process (which is when the police copy all of the data off of the phone onto another storage medium).

Presumably, had the FBI obtained an anticipatory warrant in the case that the Wall Street Journal wrote about, the company would have assisted the government in its attempts to unlock the target’s phone.

Praise for Google

The fact that Google can, in some circumstances, provide the government access to data on a locked Android phone should not be taken as evidence that Google is designing government backdoors into its software. If anything, it is a solid example of the fact that when presented with a choice between usability and security, most large companies offering services to the general public tend to lean towards usability (for example, Apple and Dropbox can provide law enforcement agencies access to users’ data stored with their respective cloud storage services).

The existence of the screen unlock pattern bypass is likely there because a large number of consumers forget their screen unlock patterns. Many of those users are probably glad that Google lets them restore access to their device (and any data on it), rather than forcing them to perform a factory reset whenever they forget their password.

However, as soon as Google provides a feature to consumers to restore access to their locked devices, the company can be forced to provide law enforcement agencies access to that same functionality. As the old saying goes, “If you build it, they will come.”

In spite of the fact that Google has prioritized usability over security, Google’s legal team has clearly put their customers’ privacy first.

First, the company has insisted on a stricter form of court order than a plain-vanilla search warrant, and then refused to provide assistance to law enforcement agencies that seek assistance without the right kind of order.

Second, by providing the government access to the Android device via a (temporary) change to the users’ Gmail password, Google has ensured that the target of the surveillance receives an automatic email notice that their password has been changed. Although the email they receive won’t make it explicit that the government has been granted access to their mobile device, it will still serve as a hint to the target that something fishy has happened.

Third, by changing the user’s password a second time, Google has prevented the government from having ongoing, real-time access to the surveillance target’s emails. There is, I believe, no law requiring Google to take this last step—Google has done it to protect the privacy of the user, and to deny the government what would otherwise be an indefinite email wiretap not approved by the courts.

For real protection you need full-disk encryption

Of the three screen lock methods available on Android (pattern, PIN, password), Google only offers a username/password based bypass for the pattern lock. If you’d rather that the police not be able to gain access to your device this way (and are comfortable with the risk of losing your data if you are locked out of your phone), I recommend not using a pattern-based screen lock, and instead using a PIN or password.

However, it’s important to understand that while locking the screen of your device with a PIN or password is a good first step towards security, it is not sufficient to protect your data. Commercially available forensic analysis tools can be used to directly copy all data off of a device and onto external media. To prevent against such forensic imaging, it is important to encrypt data stored on a device.

Since version 3.0 (Honeycomb) of the OS, Android has included support for full disk encryption, but it is not enabled by default. If you want to keep your data safe, enabling this feature is a must.

Unfortunately, Android currently uses the same PIN or password for both the screen unlock and to decrypt the disk. This design decision makes it extremely likely that users will pick a short PIN or password, since they will probably have to enter their screen unlock dozens of time each day. Entering a 16-character password before making a phone call or obtaining GPS directions is too great of a usability burden to place on most users.

Using a shorter letter/number PIN or password might be good enough for a screen unlock, but disk encryption passwords must be much, much longer to be able to withstand brute force attacks. Case in point: A tool released at the Defcon hacker conference this summer can crack the disk encryption of Android devices that are protected with 4-6 digit numeric PINs in a matter of seconds.

Hopefully, Google’s engineers will at some point add new functionality to Android to let you use a different PIN/password for the screen unlock and full disk encryption. In the meantime, users who have rooted their device can download a third-party app that will allow you to choose a different (and hopefully much longer) password for disk encryption.

What about Apple?

The recent Wall Street Journal story on Google also raises important questions about the phone unlocking assistance Apple can provide to law enforcement agencies. An Apple spokesperson told the Journal that the company “won’t release any personal information without a search warrant, and we never share anyone’s passcode. If a court orders us to retrieve data from an iPhone, we do it ourselves. We never let anyone else unlock a customer’s iPhone.”

The quote from Apple’s spokesperson confirms what others have hinted at for some time: that the company will unlock phones and extract data from them for the police. For example, an anonymous law enforcement source told CNET earlier this year that Apple has for at least three years helped police to bypass the lock code on iPhones seized during criminal investigations.

Unfortunately, we do not know the technical specifics of how Apple retrieves data from locked iPhones. It isn’t clear if they are brute-forcing short numeric lock codes, or if there exists a backdoor in iOS that the company can use to bypass the encryption. Until more is known, the only useful advice I can offer is to disable the “Simple Passcode” feature in iOS and instead use a long, alpha-numeric passcode.

By Chris Soghoian, Principal Technologist and Senior Policy Analyst, ACLU Speech, Privacy and Technology Project at 11:48am

Aug 23, 2012 | Black Technology, News

In 2008, a Reston, VA based corporation called Oceans’ Edge, Inc. applied for a patent. On March, 2012 the company’s application for an advanced mobile snooping technology suite was approved.

The patent describes a Trojan-like program that can be secretly installed on mobile phones, allowing the attacker to monitor and record all communications incoming and outgoing, as well as manipulate the phone itself. Oceans’ Edge says that the tool is particularly useful because it allows law enforcement and corporations to work around mobile phone providers when they want to surveil someone’s phone and data activity. Instead of asking AT&T for a tap, in other words, the tool embeds itself inside your phone, turning your device against you.

A former employee of Oceans’ Edge notes on his LinkedIn page that the company’s clients included the FBI, Drug Enforcement Agency, and other law enforcement.

Oddly enough, Oceans’ Edge, Inc. describes itself as an information security company on its sparsely populated website. The “About Us” page reads:

Oceans Edge Inc. (OE) is an engineering company founded in 2006 by wireless experts to design, build, deploy, and integrate Wireless Cyber Solutions.

Our team is composed of subject matter experts in the following areas:

- Wireless Cyber Security

- Mobile Application Development

- Wireless Communication Protocols

- Wireless Network Implementation

- Lawful Intercept Technology

With this expertise, we deliver engineering services and wireless technology solutions in critical mission areas for our government and commercial customers.

But while the company may offer “cyber security” solutions to government and corporations, as the website claims, the firm only has one approved patent on file with the US Patent and Trademark Office.

Remote mobile spying

The patent is for a “Mobile device monitoring and control system.” The applicants summarize the technology thusly:

Methods and apparatus, including computer program products, for surreptitiously installing, monitoring, and operating software on a remote computer controlled wireless communication device are described.

In other words, the technology works to snoop on mobile phones by secretly installing itself on phone hardware. The targeted phone is thus compromised in two ways: first, the attacker can spy on all the contents of the phone; and second, the attacker can operate the phone from afar. That’s to say, it doesn’t just let the attacker read your text messages. It also potentially lets him write them.

The summary goes on:

One aspect includes a control system for communicating programming instructions and exchanging data with the remote computer controlled wireless communication device. The control system is configured to provide at least one element selected from the group consisting of: a computer implemented device controller; a module repository in electronic communication with the device controller; a control service in electronic communication with the device controller; an exfiltration data service in electronic communication with the device controller configured to receive, store, and manage data obtained surreptitiously from the remote computer controlled wireless communication device; a listen-only recording service in electronic communication with the device controller; and a WAP gateway in electronic communication with the remote computer controlled wireless communication device.

The technology therefore also enables automated data storage of all of a phone’s activity in the attacker’s database. So if someone used this technology to spy on your phone, they would be able to use the Oceans’ Edge product to automatically store everything you do on it, to go back to later.

In case you aren’t sure who would want this kind of spook technology or why, Oceans’ Edge explains in the patent application:

A user’s employment of a mobile device, and the data stored within a mobile device, is often of interest to individuals and entities that desire to monitor and/or record the activities of a user or a mobile device. Some examples of such individuals and entities include law enforcement, corporate compliance officers, and security-related organizations. As more and more users use wireless and mobile devices, the need to monitor the usage of these devices grows as well. Monitoring a mobile device includes the collection of performance metrics, recording of keystrokes, data, files, and communications (e.g. voice, SMS (Short Message Service), network), collectively called herein “monitoring results“, in which the mobile device participates.

The application goes on to explain that the tool is beneficial to law enforcement or other customers because it allows them to avoid dealing with pesky mobile phone providers when they want to covertly spy on people’s mobile communications. Instead of the FBI going to AT&T or T-Mobile to get access to your cell data, they can just surreptitiously install this bug on your phone. They’ll get all your data — and your phone company might never know.

Mobile device monitoring can be performed using “over the air” (OTA) at the service provider, either stand-alone or by using a software agent in conjunction with network hardware such a telephone switch. Alternatively, mobile devices can be monitored by using a stand-alone agent on the device that communicates with external servers and applications. In some cases, mobile device monitoring can be performed with the full knowledge and cooperation of one of a plurality of mobile device users, the mobile device owner, and the wireless service provider. In other cases, the mobile device user or service provider may not be aware of the monitoring. In these cases, a monitoring application or software agent that monitors a mobile device can be manually installed on a mobile device to collect information about the operation of the mobile device and make said information available for later use. In some cases, this information is stored on the mobile device until it is manually accessed and retrieved. In other cases, the monitoring application delivers the information to a server or network device. In these cases, the installation, information collection, and retrieval of collected information are not performed covertly (i.e. without the knowledge of the party or parties with respect to whom the monitoring, data collection, or control, or any combination thereof, is desired, such as, but not limited to, the device user, the device owner, or the service provider). The use of “signing certificates” to authenticate software prior to installation can make covert installation of monitoring applications problematic. When software is not signed by a trusted authority, the software may not be installed, or the device user may be prompted for permission to install the software. In either case, the monitoring application is not installed covertly as required. Additionally, inspection of the mobile device can detect such a monitoring application and the monitoring application may be disabled by the device user. Alternatively, OTA message traffic may be captured using network hardware such as the telephone switch provided by a service provider. This requires explicit cooperation by the service provider, and provides covert monitoring that is limited to message information passed over the air. As a result, service provider-based monitoring schemes require expensive monitoring equipment, cooperation from the service provider, and are limited as to the types of information they can monitor.

The applicants describe some of the challenges they had to overcome, which include:

Additional challenges are present when the monitoring results are transmitted from a mobile device. First, many mobile devices are not configured to transmit and receive large amounts of information. In some instances, this is because the mobile device user has not subscribed to an appropriate data service from an information provider. In other instances, the mobile device has limited capabilities.

In other words, make sure you get that unlimited data plan, or else it’ll be really hard for the FBI to spy on your mobile phone! It’ll take up so much of your data usage that you’ll notice and maybe even complain to your mobile provider! That would be awkward.

Second, transmitting information often provides indications of mobile device activity (e.g. in the form of activity lights, battery usage, performance degradation).

Bad battery performance that the geeks at the Apple genius bar can’t explain? Maybe your device has been compromised.

Third, transmitting information wirelessly requires operation in areas of intermittent signal, with automated restart and retransmission of monitoring results if and when a signal becomes available.

The monitoring program has got to be clever enough to stop and restart every time you go out of range of your cell network, or you turn the phone off.

Fourth, many mobile devices are “pay as you go” or have detailed billing enabled at the service provider. The transmission of monitoring results can quickly use all the credit available on a pre-paid wireless plan, or result in detailed service records describing the transmission on a wireless customer’s billing statement.

When the snoops steal your information, you might have to pay for the pleasure of being spied on. That’s because your mobile phone provider might read the spying activity as your activity. After all, it’s coming from your phone.

Lastly, stored monitoring results can take up significant storage on a mobile device and the stored materials and the use of this storage can be observed by the device user.

Is there a large chunk of space on your phone that seems full, but you can’t figure out why? Perhaps a snoop tool like that devised by Oceans’ Edge, Inc. is storing data on your phone that it plans to later capture.

Given all of those potential problems, the technologists had a lot of work cut out for them. Here’s how they addressed those problems:

From the foregoing, it will be appreciated that effective covert monitoring of a mobile device requires the combination of several technologies and techniques that hide, disguise, or otherwise mask at least one aspect of the monitoring processes: the covert identification of the mobile devices to be monitored, the covert installation and control of the monitoring applications, and the covert exfiltration of collected monitoring results. As used herein, “covert exfiltration” refers to a process of moving collected monitoring results from a mobile device while it is under the control of another without their knowledge or awareness. Thus covert exfiltration processes can be those using stealth, surprise, covert, or clandestine means to relay monitoring data. “Collected monitoring results” as used herein includes any or all materials returned from a monitored mobile device to other devices, using either mobile or fixed points-of-presence. Examples of collected monitoring results include one or more of the following: command results, call information and call details, including captured voice, images, message traffic (e.g. text messaging, SMS, email), and related items such as files, documents and materials stored on the monitored mobile device. These materials may include pictures, video clips, PIM information (e.g. calendar, task list, address and telephone book), other application information such as browsing history, and device status information (e.g. device presence, cell towers/wireless transmitters/points-of-presence used, SIM data, device settings, location, profiles, and other device information). Additionally, the capability to covertly utilize a mobile device as a covertly managed camera or microphone provides other unique challenges.

Thus covert monitoring of a mobile device’s operation poses the significant technical challenges of hiding or masking the installation and operation of the monitoring application, its command and control sessions, hiding the collected monitoring results until they are exfiltrated, surreptitiously transmitting the results, and managing the billing for the related wireless services. The exemplary illustrative technology herein addresses these and other important needs.

In short, Oceans’ Edge Inc., a company founded and operating in the heart of CIA country, says it has a technology that can secretly install itself on mobile phones and push all the contents of the devices to an external database, doing so entirely under the radar of both the target and the target’s mobile provider. It even boasts that the tool allows for covertly managing phone cameras and microphones.

What kind of contracts does this company have, and with which government agencies? A cursory internet search didn’t turn up much, except for a couple of bids to work on a military information operations

program and a cyber defense

project. Neither one of those programs has an obvious link to the mobile snooping device described in the patent application.

Since we don’t know which agencies are using this technology or how, it’s hard to say to what extent this kind of secret monitoring is taking place in the US. We have some evidence suggesting that the FBI and DEA are using this tool (thanks, Chris Soghoian, for the tip). If those agencies really are using this technology, they should get warrants before they compromise anyone’s phone.

Is the government getting warrants to use this tool? We don’t know.

Oceans’ Edge Inc., like many purveyors of surveillance products, claims that its technology is only deployed for “lawful interception,” but it makes no claims about what that actually means. There’s no mention of judicial oversight, warrants, or any kind of due process. As I’ve written elsewhere on this blog, given the state of the law concerning surveillance in the digital age, we shouldn’t let our guard down simply because a company claims its surveillance tools are used lawfully. That’s because we do not know how these tools are being deployed, and yet we know that the state of surveillance law in the US at present grants the government wide latitude to infringe on our privacy in ways that are often improper or even unconstitutional.

In most cases (with a few notable exceptions), lawmakers haven’t worked to address this issue.

As we can see, surveillance technologies are developing rapidly. It’s past time for our laws to catch up.