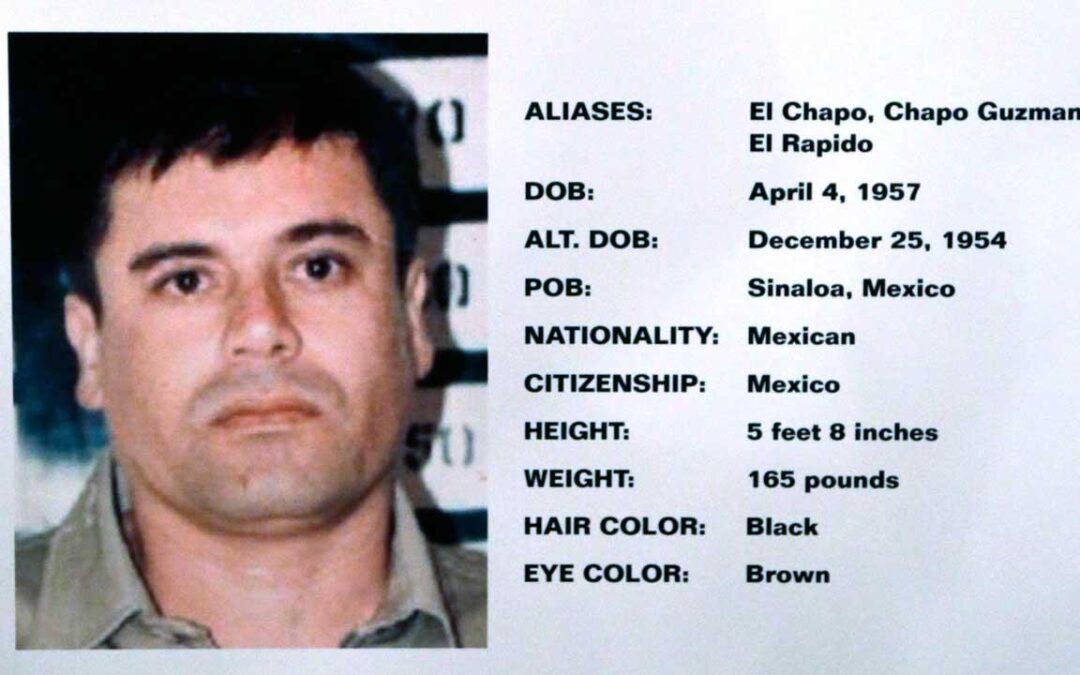

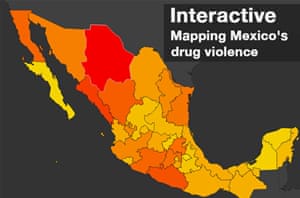

On 10 April 2006, a DC-9 jet landed in the port city of Ciudad del Carmen, on the Gulf of Mexico, as the sun was setting. Mexican soldiers, waiting to intercept it, found 128 cases packed with 5.7 tons of cocaine, valued at $100m. But something else – more important and far-reaching – was discovered in the paper trail behind the purchase of the plane by the Sinaloa narco-trafficking cartel.

During a 22-month investigation by agents from the US Drug Enforcement Administration, the Internal Revenue Service and others, it emerged that the cocaine smugglers had bought the plane with money they had laundered through one of the biggest banks in the United States: Wachovia, now part of the giant Wells Fargo.

The authorities uncovered billions of dollars in wire transfers, traveller’s cheques and cash shipments through Mexican exchanges into Wachovia accounts. Wachovia was put under immediate investigation for failing to maintain an effective anti-money laundering programme. Of special significance was that the period concerned began in 2004, which coincided with the first escalation of violence along the US-Mexico border that ignited the current drugs war.

Criminal proceedings were brought against Wachovia, though not against any individual, but the case never came to court. In March 2010, Wachovia settled the biggest action brought under the US bank secrecy act, through the US district court in Miami. Now that the year’s “deferred prosecution” has expired, the bank is in effect in the clear. It paid federal authorities $110m in forfeiture, for allowing transactions later proved to be connected to drug smuggling, and incurred a $50m fine for failing to monitor cash used to ship 22 tons of cocaine.

More shocking, and more important, the bank was sanctioned for failing to apply the proper anti-laundering strictures to the transfer of $378.4bn – a sum equivalent to one-third of Mexico’s gross national product – into dollar accounts from so-called casas de cambio (CDCs) in Mexico, currency exchange houses with which the bank did business.

“Wachovia’s blatant disregard for our banking laws gave international cocaine cartels a virtual carte blanche to finance their operations,” said Jeffrey Sloman, the federal prosecutor. Yet the total fine was less than 2% of the bank’s $12.3bn profit for 2009. On 24 March 2010, Wells Fargo stock traded at $30.86 – up 1% on the week of the court settlement.

The conclusion to the case was only the tip of an iceberg, demonstrating the role of the “legal” banking sector in swilling hundreds of billions of dollars – the blood money from the murderous drug trade in Mexico and other places in the world – around their global operations, now bailed out by the taxpayer.

At the height of the 2008 banking crisis, Antonio Maria Costa, then head of the United Nations office on drugs and crime, said he had evidence to suggest the proceeds from drugs and crime were “the only liquid investment capital” available to banks on the brink of collapse. “Inter-bank loans were funded by money that originated from the drugs trade,” he said. “There were signs that some banks were rescued that way.”

Wachovia was acquired by Wells Fargo during the 2008 crash, just as Wells Fargo became a beneficiary of $25bn in taxpayers’ money. Wachovia’s prosecutors were clear, however, that there was no suggestion Wells Fargo had behaved improperly; it had co-operated fully with the investigation. Mexico is the US’s third largest international trading partner and Wachovia was understandably interested in this volume of legitimate trade.

José Luis Marmolejo, who prosecuted those running one of the casas de cambio at the Mexican end, said: “Wachovia handled all the transfers. They never reported any as suspicious.”

“As early as 2004, Wachovia understood the risk,” the bank admitted in the statement of settlement with the federal government, but, “despite these warnings, Wachovia remained in the business”. There is, of course, the legitimate use of CDCs as a way into the Hispanic market. In 2005 the World Bank said that Mexico was receiving $8.1bn in remittances.

During research into the Wachovia Mexican case, the Observer obtained documents previously provided to financial regulators. It emerged that the alarm that was ignored came from, among other places, London, as a result of the diligence of one of the most important whistleblowers of our time. A man who, in a series of interviews with the Observer, adds detail to the documents, laying bare the story of how Wachovia was at the centre of one of the world’s biggest money-laundering operations.

Martin Woods, a Liverpudlian in his mid-40s, joined the London office of Wachovia Bank in February 2005 as a senior anti-money laundering officer. He had previously served with the Metropolitan police drug squad. As a detective he joined the money-laundering investigation team of the National Crime Squad, where he worked on the British end of the Bank of New York money-laundering scandal in the late 1990s.

Woods talks like a police officer – in the best sense of the word: punctilious, exact, with a roguish humour, but moral at the core. He was an ideal appointment for any bank eager to operate a diligent and effective risk management policy against the lucrative scourge of high finance: laundering, knowing or otherwise, the vast proceeds of criminality, tax-evasion, and dealing in arms and drugs.

Woods had a police officer’s eye and a police officer’s instincts – not those of a banker. And this influenced not only his methods, but his mentality. “I think that a lot of things matter more than money – and that marks you out in a culture which appears to prevail in many of the banks in the world,” he says.

Woods was set apart by his modus operandi. His speciality, he explains, was his application of a “know your client”, or KYC, policing strategy to identifying dirty money. “KYC is a fundamental approach to anti-money laundering, going after tax evasion or counter-terrorist financing. Who are your clients? Is the documentation right? Good, responsible banking involved always knowing your customer and it still does.”

When he looked at Wachovia, the first thing Woods noticed was a deficiency in KYC information. And among his first reports to his superiors at the bank’s headquarters in Charlotte, North Carolina, were observations on a shortfall in KYC at Wachovia’s operation in London, which he set about correcting, while at the same time implementing what was known as an enhanced transaction monitoring programme, gathering more information on clients whose money came through the bank’s offices in the City, in sterling or euros. By August 2006, Woods had identified a number of suspicious transactions relating to casas de cambio customers in Mexico.

Primarily, these involved deposits of traveller’s cheques in euros. They had sequential numbers and deposited larger amounts of money than any innocent travelling person would need, with inadequate or no KYC information on them and what seemed to a trained eye to be dubious signatures. “It was basic work,” he says. “They didn’t answer the obvious questions: ‘Is the transaction real, or does it look synthetic? Does the traveller’s cheque meet the protocols? Is it all there, and if not, why not?'”

Woods discussed the matter with Wachovia’s global head of anti-money laundering for correspondent banking, who believed the cheques could signify tax evasion. He then undertook what banks call a “look back” at previous transactions and saw fit to submit a series of SARs, or suspicious activity reports, to the authorities in the UK and his superiors in Charlotte, urging the blocking of named parties and large series of sequentially numbered traveller’s cheques from Mexico. He issued a number of SARs in 2006, of which 50 related to the casas de cambio in Mexico. To his amazement, the response from Wachovia’s Miami office, the centre for Latin American business, was anything but supportive – he felt it was quite the reverse.

As it turned out, however, Woods was on the right track. Wachovia’s business in Mexico was coming under closer and closer scrutiny by US federal law enforcement. Wachovia was issued with a number of subpoenas for information on its Mexican operation. Woods has subsequently been informed that Wachovia had six or seven thousand subpoenas. He says this was “An absurd number. So at what point does someone at the highest level not get the feeling that something is very, very wrong?”

In April and May 2007, Wachovia – as a result of increasing interest and pressure from the US attorney’s office – began to close its relationship with some of the casas de cambio. But rather than launch an internal investigation into Woods’s alerts over Mexico, Woods claims Wachovia hung its own money-laundering expert out to dry. The records show that during 2007 Woods “continued to submit more SARs related to the casas de cambio“.

In July 2007, all of Wachovia’s remaining 10 Mexican casa de cambio clients operating through London suddenly stopped doing so. Later in 2007, after the investigation of Wachovia was reported in the US financial media, the bank decided to end its remaining relationships with the Mexican casas de cambio globally. By this time, Woods says, he found his personal situation within the bank untenable; while the bank acted on one level to protect itself from the federal investigation into its shortcomings, on another, it rounded on the man who had been among the first to spot them.

On 16 June Woods was told by Wachovia’s head of compliance that his latest SAR need not have been filed, that he had no legal requirement to investigate an overseas case and no right of access to documents held overseas from Britain, even if they were held by Wachovia.

Woods’s life went into freefall. He went to hospital with a prolapsed disc, reported sick and was told by the bank that he not done so in the appropriate manner, as directed by the employees’ handbook. He was off work for three weeks, returning in August 2007 to find a letter from the bank’s compliance managing director, which was unrelenting in its tone and words of warning.

The letter addressed itself to what the manager called “specific examples of your failure to perform at an acceptable standard”. Woods, on the edge of a breakdown, was put on sick leave by his GP; he was later given psychiatric treatment, enrolled on a stress management course and put on medication.

Late in 2007, Woods attended a function at Scotland Yard where colleagues from the US were being entertained. There, he sought out a representative of the Drug Enforcement Administration and told him about the casas de cambio, the SARs and his employer’s reaction. The Federal Reserve and officials of the office of comptroller of currency in Washington DC then “spent a lot of time examining the SARs” that had been sent by Woods to Charlotte from London.

“They got back in touch with me a while afterwards and we began to put the pieces of the jigsaw together,” says Woods. What they found was – as Costa says – the tip of the iceberg of what was happening to drug money in the banking industry, but at least it was visible and it had a name: Wachovia.

In June 2005, the DEA, the criminal division of the Internal Revenue Service and the US attorney’s office in southern Florida began investigating wire transfers from Mexico to the US. They were traced back to correspondent bank accounts held by casas de cambio at Wachovia. The CDC accounts were supervised and managed by a business unit of Wachovia in the bank’s Miami offices.

“Through CDCs,” said the court document, “persons in Mexico can use hard currency and … wire transfer the value of that currency to US bank accounts to purchase items in the United States or other countries. The nature of the CDC business allows money launderers the opportunity to move drug dollars that are in Mexico into CDCs and ultimately into the US banking system.

“On numerous occasions,” say the court papers, “monies were deposited into a CDC by a drug-trafficking organisation. Using false identities, the CDC then wired that money through its Wachovia correspondent bank accounts for the purchase of airplanes for drug-trafficking organisations.” The court settlement of 2010 would detail that “nearly $13m went through correspondent bank accounts at Wachovia for the purchase of aircraft to be used in the illegal narcotics trade. From these aircraft, more than 20,000kg of cocaine were seized.”

All this occurred despite the fact that Wachovia’s office was in Miami, designated by the US government as a “high-intensity money laundering and related financial crime area”, and a “high-intensity drug trafficking area”. Since the drug cartel war began in 2005, Mexico had been designated a high-risk source of money laundering.

“As early as 2004,” the court settlement would read, “Wachovia understood the risk that was associated with doing business with the Mexican CDCs. Wachovia was aware of the general industry warnings. As early as July 2005, Wachovia was aware that other large US banks were exiting the CDC business based on [anti-money laundering] concerns … despite these warnings, Wachovia remained in business.”

On 16 March 2010, Douglas Edwards, senior vice-president of Wachovia Bank, put his signature to page 10 of a 25-page settlement, in which the bank admitted its role as outlined by the prosecutors. On page 11, he signed again, as senior vice-president of Wells Fargo. The documents show Wachovia providing three services to 22 CDCs in Mexico: wire transfers, a “bulk cash service” and a “pouch deposit service”, to accept “deposit items drawn on US banks, eg cheques and traveller’s cheques”, as spotted by Woods.

“For the time period of 1 May 2004 through 31 May 2007, Wachovia processed at least $$373.6bn in CDCs, $4.7bn in bulk cash” – a total of more than $378.3bn, a sum that dwarfs the budgets debated by US state and UK local authorities to provide services to citizens.

The document gives a fascinating insight into how the laundering of drug money works. It details how investigators “found readily identifiable evidence of red flags of large-scale money laundering”. There were “structured wire transfers” whereby “it was commonplace in the CDC accounts for round-number wire transfers to be made on the same day or in close succession, by the same wire senders, for the … same account”.

Over two days, 10 wire transfers by four individuals “went though Wachovia for deposit into an aircraft broker’s account. All of the transfers were in round numbers. None of the individuals of business that wired money had any connection to the aircraft or the entity that allegedly owned the aircraft. The investigation has further revealed that the identities of the individuals who sent the money were false and that the business was a shell entity. That plane was subsequently seized with approximately 2,000kg of cocaine on board.”

Many of the sequentially numbered traveller’s cheques, of the kind dealt with by Woods, contained “unusual markings” or “lacked any legible signature”. Also, “many of the CDCs that used Wachovia’s bulk cash service sent significantly more cash to Wachovia than what Wachovia had expected. More specifically, many of the CDCs exceeded their monthly activity by at least 50%.”

Recognising these “red flags”, the US attorney’s office in Miami, the IRS and the DEA began investigating Wachovia, later joined by FinCEN, one of the US Treasury’s agencies to fight money laundering, while the office of the comptroller of the currency carried out a parallel investigation. The violations they found were, says the document, “serious and systemic and allowed certain Wachovia customers to launder millions of dollars of proceeds from the sale of illegal narcotics through Wachovia accounts over an extended time period. The investigation has identified that at least $110m in drug proceeds were funnelled through the CDC accounts held at Wachovia.”

The settlement concludes by discussing Wachovia’s “considerable co-operation and remedial actions” since the prosecution was initiated, after the bank was bought by Wells Fargo. “In consideration of Wachovia’s remedial actions,” concludes the prosecutor, “the United States shall recommend to the court … that prosecution of Wachovia on the information filed … be deferred for a period of 12 months.”

But while the federal prosecution proceeded, Woods had remained out in the cold. On Christmas Eve 2008, his lawyers filed tribunal proceedings against Wachovia for bullying and detrimental treatment of a whistleblower. The case was settled in May 2009, by which time Woods felt as though he was “the most toxic person in the bank”. Wachovia agreed to pay an undisclosed amount, in return for which Woods left the bank and said he would not make public the terms of the settlement.

After years of tribulation, Woods was finally formally vindicated, though not by Wachovia: a letter arrived from John Dugan, the comptroller of the currency in Washington DC, dated 19 March 2010 – three days after the settlement in Miami. Dugan said he was “writing to personally recognise and express my appreciation for the role you played in the actions brought against Wachovia Bank for violations of the bank secrecy act … Not only did the information that you provided facilitate our investigation, but you demonstrated great personal courage and integrity by speaking up. Without the efforts of individuals like you, actions such as the one taken against Wachovia would not be possible.”

The so-called “deferred prosecution” detailed in the Miami document is a form of probation whereby if the bank abides by the law for a year, charges are dropped. So this March the bank was in the clear. The week that the deferred prosecution expired, a spokeswoman for Wells Fargo said the parent bank had no comment to make on the documentation pertaining to Woods’s case, or his allegations. She added that there was no comment on Sloman’s remarks to the court; a provision in the settlement stipulated Wachovia was not allowed to issue public statements that contradicted it.

But the settlement leaves a sour taste in many mouths – and certainly in Woods’s. The deferred prosecution is part of this “cop-out all round”, he says. “The regulatory authorities do not have to spend any more time on it, and they don’t have to push it as far as a criminal trial. They just issue criminal proceedings, and settle. The law enforcement people do what they are supposed to do, but what’s the point? All those people dealing with all that money from drug-trafficking and murder, and no one goes to jail?”

One of the foremost figures in the training of anti-money laundering officers is Robert Mazur, lead infiltrator for US law enforcement of the Colombian Medellín cartel during the epic prosecution and collapse of the BCCI banking business in 1991 (his story was made famous by his memoir, The Infiltrator, which became a movie).

Mazur, whose firm Chase and Associates works closely with law enforcement agencies and trains officers for bank anti-money laundering, cast a keen eye over the case against Wachovia, and he says now that “the only thing that will make the banks properly vigilant to what is happening is when they hear the rattle of handcuffs in the boardroom”.

Mazur said that “a lot of the law enforcement people were disappointed to see a settlement” between the administration and Wachovia. “But I know there were external circumstances that worked to Wachovia’s benefit, not least that the US banking system was on the edge of collapse.”

What concerns Mazur is that what law enforcement agencies and politicians hope to achieve against the cartels is limited, and falls short of the obvious attack the US could make in its war on drugs: go after the money. “We’re thinking way too small,” Mazur says. “I train law enforcement officers, thousands of them every year, and they say to me that if they tried to do half of what I did, they’d be arrested. But I tell them: ‘You got to think big. The headlines you will be reading in seven years’ time will be the result of the work you begin now.’ With BCCI, we had to spend two years setting it up, two years doing undercover work, and another two years getting it to trial. If they want to do something big, like go after the money, that’s how long it takes.”

But Mazur warns: “If you look at the career ladders of law enforcement, there’s no incentive to go after the big money. People move every two to three years. The DEA is focused on drug trafficking rather than money laundering. You get a quicker result that way – they want to get the traffickers and seize their assets. But this is like treating a sick plant by cutting off a few branches – it just grows new ones. Going after the big money is cutting down the plant – it’s a harder door to knock on, it’s a longer haul, and it won’t get you the short-term riches.”

The office of the comptroller of the currency is still examining whether individuals in Wachovia are criminally liable. Sources at FinCEN say that a so-called “look-back” is in process, as directed by the settlement and agreed to by Wachovia, into the $378.4bn that was not directly associated with the aircraft purchases and cocaine hauls, but neither was it subject to the proper anti-laundering checks. A FinCEN source says that $20bn already examined appears to have “suspicious origins”. But this is just the beginning.

Antonio Maria Costa, who was executive director of the UN’s office on drugs and crime from May 2002 to August 2010, charts the history of the contamination of the global banking industry by drug and criminal money since his first initiatives to try to curb it from the European commission during the 1990s. “The connection between organised crime and financial institutions started in the late 1970s, early 1980s,” he says, “when the mafia became globalised.”

Until then, criminal money had circulated largely in cash, with the authorities making the occasional, spectacular “sting” or haul. During Costa’s time as director for economics and finance at the EC in Brussels, from 1987, inroads were made against penetration of banks by criminal laundering, and “criminal money started moving back to cash, out of the financial institutions and banks. Then two things happened: the financial crisis in Russia, after the emergence of the Russian mafia, and the crises of 2003 and 2007-08.

“With these crises,” says Costa, “the banking sector was short of liquidity, the banks exposed themselves to the criminal syndicates, who had cash in hand.”

Costa questions the readiness of governments and their regulatory structures to challenge this large-scale corruption of the global economy: “Government regulators showed what they were capable of when the issue suddenly changed to laundering money for terrorism – on that, they suddenly became serious and changed their attitude.”

Hardly surprising, then, that Wachovia does not appear to be the end of the line. In August 2010, it emerged in quarterly disclosures by HSBC that the US justice department was seeking to fine it for anti-money laundering compliance problems reported to include dealings with Mexico.

“Wachovia had my résumé, they knew who I was,” says Woods. “But they did not want to know – their attitude was, ‘Why are you doing this?’ They should have been on my side, because they were compliance people, not commercial people. But really they were commercial people all along. We’re talking about hundreds of millions of dollars. This is the biggest money-laundering scandal of our time.

“These are the proceeds of murder and misery in Mexico, and of drugs sold around the world,” he says. “All the law enforcement people wanted to see this come to trial. But no one goes to jail. “What does the settlement do to fight the cartels? Nothing – it doesn’t make the job of law enforcement easier and it encourages the cartels and anyone who wants to make money by laundering their blood dollars. Where’s the risk? There is none.

“Is it in the interest of the American people to encourage both the drug cartels and the banks in this way? Is it in the interest of the Mexican people? It’s simple: if you don’t see the correlation between the money laundering by banks and the 30,000 people killed in Mexico, you’re missing the point.”

Woods feels unable to rest on his laurels. He tours the world for a consultancy he now runs, Hermes Forensic Solutions, counselling and speaking to banks on the dangers of laundering criminal money, and how to spot and stop it. “New York and London,” says Woods, “have become the world’s two biggest laundries of criminal and drug money, and offshore tax havens. Not the Cayman Islands, not the Isle of Man or Jersey. The big laundering is right through the City of London and Wall Street.

“After the Wachovia case, no one in the regulatory community has sat down with me and asked, ‘What happened?’ or ‘What can we do to avoid this happening to other banks?’ They are not interested. They are the same people who attack the whistleblowers and this is a position the [British] Financial Services Authority at least has adopted on legal advice: it has been advised that the confidentiality of banking and bankers takes primacy over the public information disclosure act. That is how the priorities work: secrecy first, public interest second.

“Meanwhile, the drug industry has two products: money and suffering. On one hand, you have massive profits and enrichment. On the other, you have massive suffering, misery and death. You cannot separate one from the other.

“What happened at Wachovia was symptomatic of the failure of the entire regulatory system to apply the kind of proper governance and adequate risk management which would have prevented not just the laundering of blood money, but the global crisis.”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/apr/03/us-bank-mexico-drug-gangs