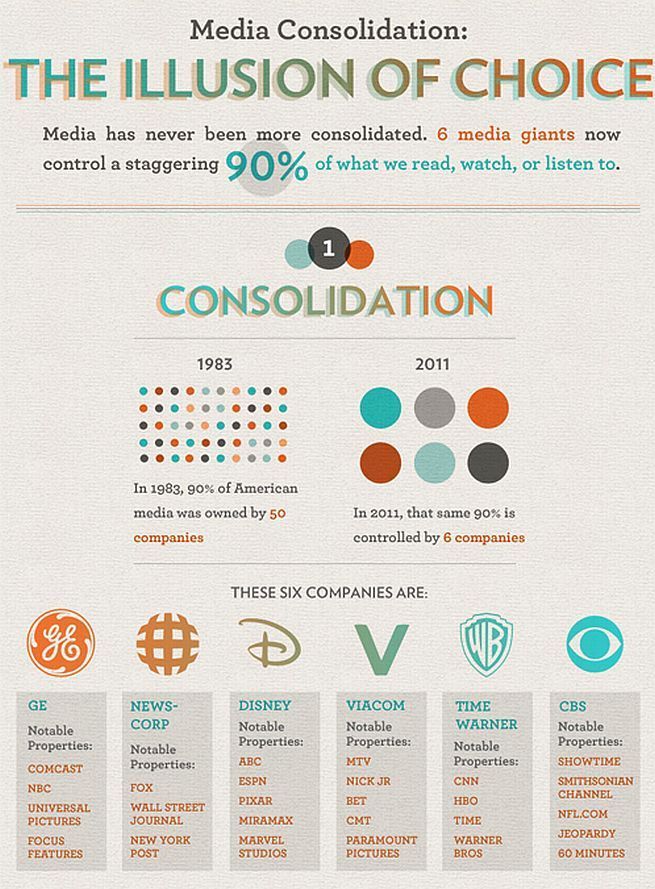

Operation Mockingbird is a large-scale program of the United States Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that began in the early 1950s and attempted to manipulate news media for propaganda purposes. It funded student and cultural organizations and magazines as front organizations.

Operation Mockingbird

According to writer Deborah Davis, Operation Mockingbird recruited leading American journalists into a propaganda network and oversaw the operations of front groups. CIA support of front groups was exposed after a 1967 Ramparts magazine article reported that the National Student Association received funding from the CIA. In the 1970s, Congressional investigations and reports also revealed Agency connections with journalists and civic groups. None of these reports, however, mentions by name an Operation Mockingbird coordinating or supporting these activities.

A Project Mockingbird is mentioned in the CIA Family Jewels report, compiled in the mid-1970s. According to the declassified version of the report released in 2007, Project Mockingbird involved the wire-tapping of two American journalists for several months in the early 1960s.

History

In the early years of the Cold War, efforts were made by the governments of the Soviet Union and the United States to use media companies to influence public opinion internationally. Reporter Deborah Davis claimed in her 1979 biography of Katharine Graham, owner of The Washington Post, (Katharine the Great), that the CIA ran an “Operation Mockingbird” during this time.[2] Davis claimed that the International Organization of Journalists was created as a Communist front organization and “received money from Moscow and controlled reporters on every major newspaper in Europe, disseminating stories that promoted the Communist cause.”[3] Davis claimed that Frank Wisner, director of the Office of Policy Coordination (a covert operations unit created in 1948 by the United States National Security Council) had created Operation Mockingbird in response to the International Organization of Journalists, recruiting Phil Graham from The Washington Post to run the project within the industry. According to Davis, “By the early 1950s, Wisner ‘owned’ respected members of The New York Times, Newsweek, CBS and other communications vehicles.”[4] Davis claimed that after Cord Meyer joined the CIA in 1951, he became Operation Mockingbird’s “principal operative.”[5]

In a 1977 Rolling Stone magazine article, “The CIA and the Media,” reporter Carl Bernstein wrote that by 1953, CIA Director Allen Dulles oversaw the media network, which had major influence over 25 newspapers and wire agencies.[6] Its usual modus operandi was to place reports, developed from CIA-provided intelligence, with cooperating or unwitting reporters. Those reports would be repeated or cited by the recipient reporters and would then, in turn, be cited throughout the media wire services. These networks were run by people with well-known liberal but pro-American-big-business and anti-Soviet views, such as William S. Paley (CBS), Henry Luce (Time and Life), Arthur Hays Sulzberger (The New York Times), Alfred Friendly (managing editor of The Washington Post), Jerry O’Leary (The Washington Star), Hal Hendrix (Miami News), Barry Bingham, Sr. (Louisville Courier-Journal), James S. Copley (Copley News Services) and Joseph Harrison (The Christian Science Monitor).[6]

Congressional investigations

After the Watergate scandal in 1972–1974, the U.S. Congress became concerned over possible presidential abuse of the CIA. This concern reached its height when reporter Seymour Hersh published an exposé of CIA domestic surveillance in 1975.[7] Congress authorized a series of Congressional investigations into Agency activities from 1975 to 1976. A wide range of CIA operations were examined in these investigations, including CIA ties with journalists and numerous private voluntary organizations. None of the resulting reports, however, refer to an Operation Mockingbird.

The most extensive discussion of CIA relations with news media from these investigations is in the Church Committee‘s final report, published in April 1976. The report covered CIA ties with both foreign and domestic news media.

For foreign news media, the report concluded that:

The CIA currently maintains a network of several hundred foreign individuals around the world who provide intelligence for the CIA and at times attempt to influence opinion through the use of covert propaganda. These individuals provide the CIA with direct access to a large number of newspapers and periodicals, scores of press services and news agencies, radio and television stations, commercial book publishers, and other foreign media outlets.[8]

For domestic media, the report states:

Approximately 50 of the [Agency] assets are individual American journalists or employees of U.S. media organizations. Of these, fewer than half are “accredited” by U.S. media organizations … The remaining individuals are non-accredited freelance contributors and media representatives abroad … More than a dozen United States news organizations and commercial publishing houses formerly provided cover for CIA agents abroad. A few of these organizations were unaware that they provided this cover.[8]

CIA response

Prior to the release of the Church report, the CIA had already begun restricting its use of journalists. According to the report, former CIA director William Colby informed the committee that in 1973 he had issued instructions that “As a general policy, the Agency will not make any clandestine use of staff employees of U.S. publications which have a substantial impact or influence on public opinion.”[9]

In February 1976, Director George H. W. Bush announced an even more restrictive policy: “effective immediately, CIA will not enter into any paid or contractual relationship with any full-time or part-time news correspondent accredited by any U.S. news service, newspaper, periodical, radio or television network or station.[10]

By the time the Church Committee Report was completed, all CIA contacts with accredited journalists had been dropped. The Committee noted, however, that “accredited correspondent” meant the ban was limited to individuals “formally authorized by contract or issuance of press credentials to represent themselves as correspondents” and that non-contract workers who did not receive press credentials, such as stringers or freelancers, were not included.

Mocking Us Now, But it’s Not Their First Rodeo

Mocking Us Since 1968

THE NEWS BENDERS

Other coverage

In a 1977 Rolling Stone magazine article, “The CIA and the Media,” reporter Carl Bernstein claims that the Church Committee report “covered up” CIA relations with news media, and names a number of journalists who, he says, worked with the CIA.[11] Like the Church Committee report, however, Bernstein does not refer to any Operation Mockingbird.

Project Mockingbird

In 2007 a CIA report was declassified that is titled the Family Jewels.[12] Compiled by the CIA in 1973, it refers to a Project Mockingbird and describes a wiretap of journalists. The report was compiled at the request of then CIA director James R. Schlesinger.

According to the report:

Project Mockingbird, a telephone intercept activity, was conducted between 12 March 1963 and 15 June 1963, and targeted two Washington based newsmen who, at the time, had been publishing news articles based on, and frequently quoting, classified materials of this Agency and others, including Top Secret and Special Intelligence.[13]

The wiretap was authorized by CIA director John A. McCone, “in coordination with the Attorney General (Mr. Robert Kennedy), the Secretary of Defense (Mr. Robert McNamara), and the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency (Gen. Joseph Carroll).” [13]

An internal CIA biography of McCone by CIA Chief Historian David Robarge, made public under an FOIA request, identified the two reporters as Robert S. Allen and Paul Scott.[14] Their syndicated column, “The Allen-Scott Report,” appeared in as many as three hundred papers at the height of its popularity.[15]

See also

- CIA influence on public opinion

- Congress for Cultural Freedom

- Propaganda in the United States

- Psychological warfare

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

- White propaganda

Historical studies of the CIA

- Wilford, Hugh (2008). The Mighty Wurlitzer: How the CIA Played America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02681-0.

- Saunders, Frances Stonor (1999). Who Paid the Piper?: CIA and the Cultural Cold War. London : Granata Books. ISBN 978-1-86207-029-5.

- Thomas, Evan (1995). The very best men, four men dared: the early years of the CIA. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81025-6.

- Ranelagh, John (1987). The agency: the rise and decline of the CIA. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-63994-5.

- Weiner, Tim (2007). Legacy of ashes: the history of the CIA. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51445-3.

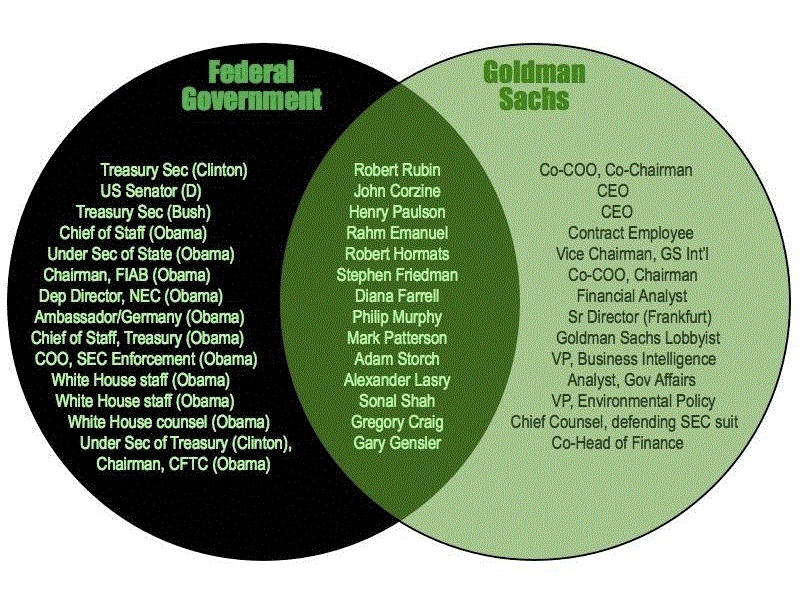

The ‘Revolving Door’ Concept

Politics to Private

And Back Again

Vizualized

References^ Armonk, NY (2004). “MOCKINGBIRD, Project”. Encyclopedia of intelligence and counterintelligence (First ed.). Routledge. p. 432. ISBN 0765680688. A Cold War-era CIA propaganda campaign, Project MOCKINGBIRD was begun in the late 1940s under Frank Wisner, director of the Office of Policy Coordination. Project MOCKINGBIRD sought to manipulate media coverage of the Cold War by recruiting foreign and domestic journalists to serve as clandestine propaganda agents for the United States. Enjoying mixed success in the late 1950s and 1960s, the program was ended in the 1970s due to mounting popular opposition to the CIA’s cover operations and domestic activities.

- ^ Davis, Deborah (1979). Katharine The Great: Katharine Graham and The Washington Post. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0151467846.

- ^ Davis 138-140

- ^ Deborah Davis (1979). Katharine the Great. pp. 137–138.

- ^ Deborah Davis (1979). Katharine the Great. p. 226.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Carl Bernstein (20 October 1977). “CIA and the Media”. Rolling Stone Magazine.

- ^ The surveillance, known as Operation CHAOS, was aimed at determining whether American opposition to the Vietnam war was being financed or manipulated by foreign governments. Ranelagh, 571-575.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Church Committee Final Report, Vol 1: Foreign and Military Intelligence, p. 455

- ^ Church Committee Final Report, Vol 1: Foreign and Military Intelligence, p. 196

- ^ Church Committee Final Report, Vol 1: Foreign and Military Intelligence, p. 454

- ^ The article, The CIA and the Media”, is available on Bernstein’s website.

- ^ “Family Jewels”. FOIA Electronic Reading Room. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2016-12-14.. A searchable pdf of the report is available at the website of George Washington University’s National Security Archive.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Family Jewels” Report, p. 22

- ^ Robarge, David (2005). John McCone as Director of Central Intelligence, 1961-1965 (part 2). Center for the Study of Intelligence. pp. 328–329. Retrieved 2016-02-14.

- ^ “Long-ago wiretap inspires a battle with the CIA for more information”. Washington Post. Retrieved 2016-12-12.