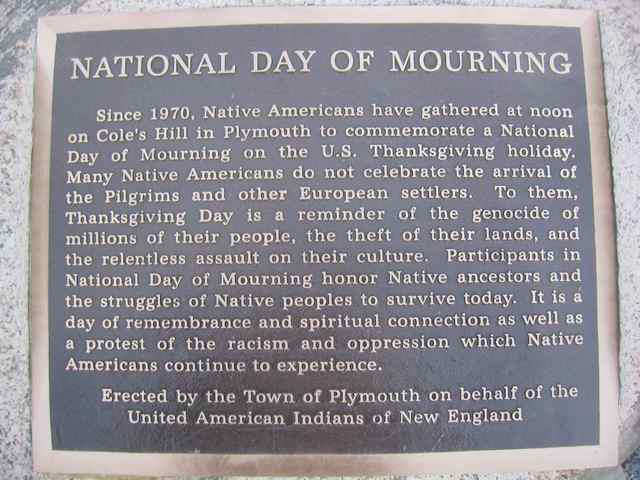

The National Day of Mourning is an annual protest organized since 1970 by Native Americans of New England on the fourth Thursday of November, the same day as Thanksgiving in the United States. It coincides with an unrelated but similar protest, Unthanksgiving Day, held on the West Coast.

The organizers consider the national holiday of Thanksgiving Day as a reminder of the democide and continued suffering of the Native American peoples. Participants in the National Day of Mourning honor Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today. They want to educate Americans about history. The event was organized in a period of Native American activism and general cultural protests. The protest is organized by the United American Indians of New England (UAINE). Since it was first organized, social changes have resulted in major revisions to the portrayal of United States history, the government’s and settlers’ relations with Native American peoples, and renewed appreciation for Native American culture.

Background

The United American Indians of New England (UAINE) organized their protest to bring publicity to the continued misrepresentation of Native American and colonial experience. They believed that people needed to be educated about what happened when the Pilgrims arrived in North America.

A century ago heavy immigration brought millions of southern and eastern Europeans to the United States. Educators and civic groups thought it necessary to assimilate the new citizens. The new arrivals were taught to view the Pilgrims as models for their own families. The tale of the “First Thanksgiving” was an essential element of this curriculum. The story of the Native Americans and Pilgrims sharing a meal of turkey became part of United States tradition. The story tells of the mutually beneficial relationship between these groups.

UAINE, by contrast, says that the Pilgrims did not find a new and empty land. Every inch of land they claimed was Indian land. They also say that the Pilgrims immigrated as part of a commercial venture and that they introduced sexism, racism, anti-homosexual bigotry, jails, and the class system.[1]

Governor John Winthrop proclaimed the first official “Day of Thanksgiving” in 1637 to celebrate the return of men that had gone to Mystic, Connecticut to fight against the Pequot, an action that resulted in the deaths of more than 700 Pequot women, children, and men, which their people called a massacre. In 1863, during the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln authorized that the fourth Thursday of November be set aside to give thanks and praise for the nation’s blessings. Thanksgiving became part of American culture.

UAINE believes that the Native American and colonial experience continue to be misrepresented. It asks why the “First Thanksgiving” was not celebrated or related back to the first colony at Jamestown. According to UAINE, the circumstances at Jamestown were too terrible to be used as a national myth. The settlers turned to cannibalism to survive. The UAINE used the National Day of Mourning to educate people about the history of the Wampanoag people. UAINE representatives say the only true element of the Thanksgiving story is that the pilgrims would not have survived their first years in New England without the aid of the Wampanoag.[2]

History

Since 1921, the 300th year after the first Thanksgiving, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts stages an annual reenactment of Thanksgiving. People gather at a church on the site of the Pilgrims’ original meeting house, in 17th century costume. After prayers and a sermon, they march to Plymouth Rock. This annual event had become a tourist attraction.

The UNAINE organized the first National Day of Mourning on the 350th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ arrival on Wampanoag land. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts planned to celebrate friendly relations between English ancestors and the Wampanoag. Wampanoag leader Frank James, also known as Wamsutta, was invited to make a speech at the celebration.[3] But, when the anniversary planners reviewed his speech in advance, they decided it was not appropriate for the celebration. The reason given was, “…the theme of the anniversary celebration is brotherhood and anything inflammatory would have been out of place.” (Source: UAINE)

Wamsutta based his speech on a Pilgrim’s account of the first year on Indian land. The book recounted the opening of graves, taking the Indians’ corn and bean supplies, and selling Wampanoag as slaves for 220 shillings each.[citation needed] After receiving a revised speech, written by a public relations person, Wamsutta decided he would not attend the celebration. To protest the silencing of the American Indian people, he and his supporters went to neighboring Cole’s Hill, near the statue of Massasoit, the leader of the Wampanoag when the Pilgrims landed. Overlooking the Plymouth Harbour and the Mayflower replica, Wamsutta gave his speech. This was the first National Day of Mourning.

Later protests

Today,[when?] the UNAINE continues leading the National Day of Mourning protest in Plymouth. The son of the founder, James, participates as well. The more recent protests have been held on Cole’s Hill and a location overlooking Plymouth Rock. The organizers have been joined by other minority activists in protest as well. Typically several hundred protesters appear. The protest generally begins at 12:00 noon on Thanksgiving Day with a march through the historic district of Plymouth. All are welcome, but the UNAINE remind participants that this is a day when the Native people speak about their history and struggles, including contemporary ones. Speakers are by invitation only. Following the march and the speeches, they have a social time. Guests are asked to bring non-alcoholic beverages, desserts, fresh fruits and vegetables, or pre-cooked items.

In 1996 the Latinos for Social Change marched to the Plymouth Commons at the same time the Mayflower Society had their Pilgrim Progress parade, to show support of UAINE. The police rerouted the Pilgrim parade to avoid conflict. In 1997 the Pilgrim Progress parade was held earlier and went undisturbed.

In 1997 those who gathered to commemorate the 28th National Day of Mourning had a more difficult time. State troopers and police met the protesters. Some accounts state that pepper spray was used on children and the elderly.[citation needed] Twenty-five people were arrested on charges ranging from battery on an officer to assembling without a permit. In an effort to avoid another conflict, the state reached a settlement with UNAINE in October 1998. It stated the UNAINE were allowed to march without a permit, as long as they gave the town advanced notice.

The 35th National Day of Mourning was held on Thursday, November 25, 2004, and was dedicated to Leonard Peltier, a Native American activist convicted and sentenced to two consecutive terms of life imprisonment for first degree murder in the shooting of two FBI agents. Many American Indians and supporters gathered again at the top of Coles Hill, overlooking Plymouth Rock. They honored their Native ancestors and the struggles of Native peoples to survive today.

Will the protest ever end?

According to a speech by Moonanum James, Co-Leader of UNAINE, at the 29th National Day of Mourning, November 26, 1998:[4]

Some ask us: Will you ever stop protesting? Some day we will stop protesting: We will stop protesting when the merchants of Plymouth are no longer making millions of dollars off the blood of our slaughtered ancestors. We will stop protesting when we can act as sovereign nations on our own land without the interference of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and what Sitting Bull called the “favorite ration chiefs”. When corporations stop polluting our mother, the earth. When racism has been eradicated. When the oppression of Two-Spirited people is a thing of the past. We will stop protesting when homeless people have homes and no child goes to bed hungry. When police brutality no longer exists in communities of color. We will stop protesting when Leonard Peltier and Mumia Abu-Jamal and the Puerto Rican independentistas and all the political prisoners are free. Until then, the struggle will continue.

References

- ^ “United American Indians of New England”. Uaine.org. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ “First ‘National Day of Mourning’ Held in Plymouth”. Mass Moments. 2005-01-01. Retrieved 2009-04-09.

- ^ Pilgrim Hall Museum

- ^ Speech by Moonanum James, Co-Leader of United American Indians of New England at the 29th National Day of Mourning, November 26, 1998

Bibliography

- Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies by Jared Diamond (1997).

- “Death by Disease” by Ann F. Ramenofsky in “Archaeology” (March/April 1992).

- Mayflower: A Story of Courage, Community, and War by Nathaniel Philbrick (2006).